Module Overview

Module Scope

Game Engines are incredibly complex, with many distinct yet interacting parts. This module will not tell you how to build a game engine from scratch. To have a module that covered building a game engine we would first need to have modules covering the mathematics involved, simulating physics, rendering, sound engines, asset management, AI and many, many other topics. We are not in a position to do this.

What we will do instead is discuss various components commonly found in game engines - what they do, how they work, what they are used for, etc.

Definition of a Game Engine

A game engine is “a piece of software designed for the creation and development of video games”. It offers a number of components and/or tools which can be (re)used to economise game development.

Core functionality typically provided by a game engine includes:

- rendering engine (2D/ 3D)

- scene graph

- collision detection (and response)

- physics engine

- scripting

- animation

- artificial intelligence

- sound

- networking

- streaming

- memory management

- threading

Game engines may also provide development tools and/or an integrated development environment to aid developers.

Some game engines only provide real-time 3D rendering capabilities (providing attachment hooks for the other types of needed game functionality). Such engines are generally referred to as a graphics engine or rendering engine.

Platform and Hardware Abstraction

Many game engines provide platform abstraction (i.e. they can be run multiple platforms – including PCs, consoles, handhelds, mobile devices, etc.).

Typically the rendering system in a game engine is built on top of a defined graphics API (e.g. Direct3D or OpenGL) providing access to the GPU.

Other libraries such as DirectX, OpenAL, etc. may also be supported to provide hardware-independent access to input devices, sound cards, network cards, physics accelerators, etc.

Component-based Architectures

Extensibility within a game engine is important given the diverse and progressive nature of game development. As such, many game engines adopt a component-based architecture, permitting engine components to be replaced or extended (either by the developer or using specialised middleware components).

Common middleware components include: Havok (physics), FMOD (sound), Scaleform GFx (UI), SpeedTree (trees/vegetation), Bink (video), Granny 3D (content/animation), etc.

Engine Architecture

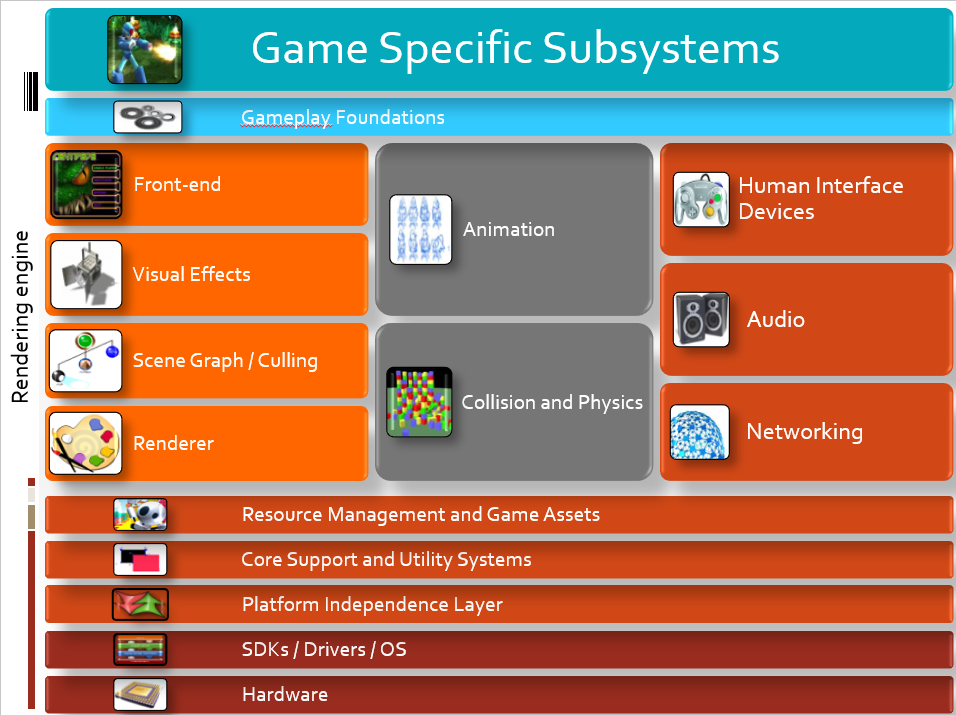

There is no standard architecture for game engines. The image below is a good generic model.

Hardware

The target hardware layer on which the game will run. A game engine may be capable of running on top of a number of hardware layers.

SDKs/Drivers/OS

Typically some means of communicating with the underlying hardware is needed. This can be accomplished using either device drivers or through APIs exposed by the OS.

In some cases, e.g. PCs, the OS strongly controls execution of the game engine (which is one executing process amongst many).

Most game engines use 3rd party SDKs to provide access to:

- Ready made data-structures and algorithms (e.g. STL or Boost in C++)

- Graphics hardware (e.g. DirectX or OpenGL)

- Collision detection and Physics (e.g. Havok, PhysX or ODE)

- etc.

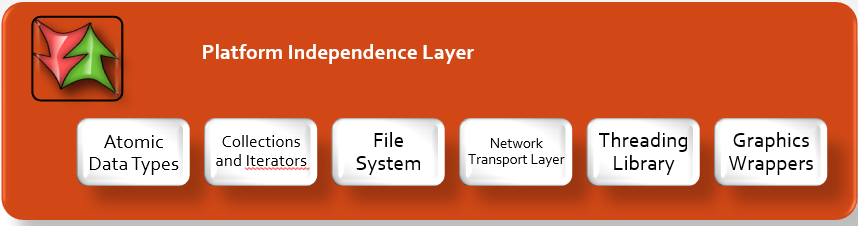

Platform Independence

Game engines which can run across multiple platforms often provide an abstraction layer hiding platform specific differences from higher-level layers.

The platform independence layer assures that standard data types, libraries, fundamental APIs, etc. offer consistent behaviour across the different supported platforms.

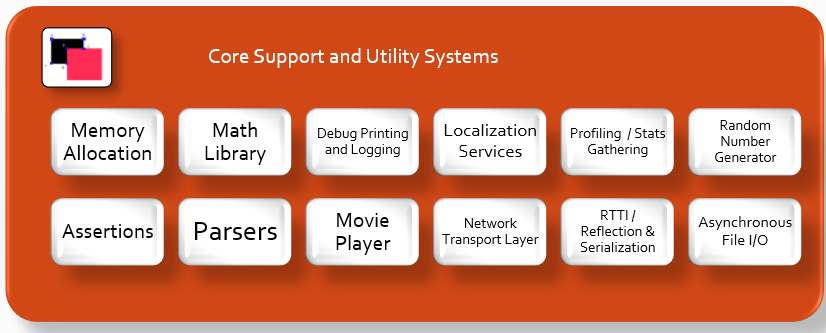

Core Systems

In order to function game engines typically depend upon underlying utility and support classes. Depending upon the game engine, this might include:

Game Assets

The resource manager provides a unified means of accessing the different types of game asset and other engine input data, including but not necessarily limited to model meshes, textures, fonts, skeletal animation data, game/world maps, etc.

Rendering Engine

The rendering engine within a game engine tends to be a large and complex component which is often decomposed into separate layers

Renderer

This component encapsulates all the raw rendering facilities of the engine, providing a means of rendering a collection of geometric primitives as quickly as possible.

Supported geometric primitives may include triangle meshes, line lists, point lists, particles, etc.

This component typically accesses the graphics device interface (possibly through a defined platform independence layer) and acts to configure the hardware state and game shaders using some defined material system and dynamic lighting system.

Scene Graph/Culling

It is the job of the scene graph to limit the number of geometric primitives sent to the renderer based on some form of visibility determination.

Typically some form of world spatial decomposition (bsp tree, bounding volume hierarchy, etc.) is employed to build a set of potentially visible objects.

Visual Effects

The rendering engine might provide support for the following types of visual effect:

- Particle effects

- Decal system

- Dynamic shadows

- Light/environmental mapping

- Full-screen post render effects (e.g. HDR, FSAA, colour correction, etc.).

Front End

A front end component provides a means of rendering 2D graphics (possibly overlaid on top of a 3D scene), providing:

- Game front end and menus

- In game Head-up-display (HUD)

- In game graphical user interface (e.g. for inventory screens, etc.)

- Debugging and other tools (e.g. console)

Collisions & Physics

Whilst collision detection and a real-time dynamics simulator can be separate entities, they are often found together given the interdependence of physics on collision detection. Given the complexity of both areas, most engines rely upon a 3rd party SDK (e.g. Havok, etc.).

A collision detection system is often of use within a wide range of non-physics related component.

Animation

Most current game engines support skeletal animation, permitting a mesh to be posed using a system of bones. Poses are typically interpolated or combined to produce a palette of matrices used to render the mesh parts (a process known as skinning).

Human Interface Devices

Games often support a number of different forms of player interface device, including:

- Keyboard and Mouse

- Gamepad

- Specialised Controllers (e.g. Wii Fit Board, dance pads, steering wheels).

It is often the role of this component to abstract the mapping of physical controls and logical game functions. The component may also embed support for detecting multiple simultaneous button presses and/or input sequences, etc.

Audio

The sophistication of audio engines between different game engines differs considerably. More advanced audio engines offer wide support for different input sound formats, including streaming, and output speaker arrangements.

Additionally, different forms of playback support, including audio effects, may also be supported.

Networking

Game engines typically provide support permitting multiple computers/ consoles to be linked together in some form of mutli-player game. This is a different environment to massively multiplayer online games (MMOGs) where thousands of players are typically managed using a server farm.

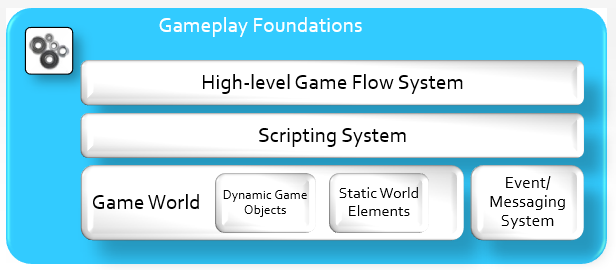

Gameplay Foundations

Gameplay refers to the actions which take place within the game. Gameplay is either implemented using the same language as that used to create the underlying game engine, or through a higher-level scripting language, or some combination of both. The gameplay foundations layer offers utilities of use to gameplay formation and a means of readily accessing some of the lower-level engine components.

Game World

The gameplay foundations layer may define the game world structure in terms of both static (e.g. background geometry) and dynamic objects (e.g. NPCs, rigid bodies subject to physics).

Event / Messaging System

In order to permit game objects to communicate and interact an event based messaging system is often employed.

Scripting System

A scripting system may be employed in order to provide more rapid, accessible and convenient development of gameplay rules and content. Typically using an interpreted scripting language avoids the need to rebuild the code base given a gameplay change.

High-Level Game Flow System

High-level control mechanisms, such as finite-state machines, etc. may be embedded within the gameplay foundations layer and made avaiable to the game specific sub-systems.