A Priori

There are a couple of basic techniques we can use to try to avoid tunnelling. We can make the speed of objects low enough that they can never tunnel through another object and we can make sure every object is too big to tunnel through. This is hardly a satisfying approach, the last thing we want to do in a game is limit movement speed and clutter the screen with huge objects just so the objects don’t tunnel through each other.

Instead we use a more complex approach known as continious collision detection.

Continuous Collision Detection

(swiped from https://www.toptal.com/game/video-game-physics-part-ii-collision-detection-for-solid-objects)

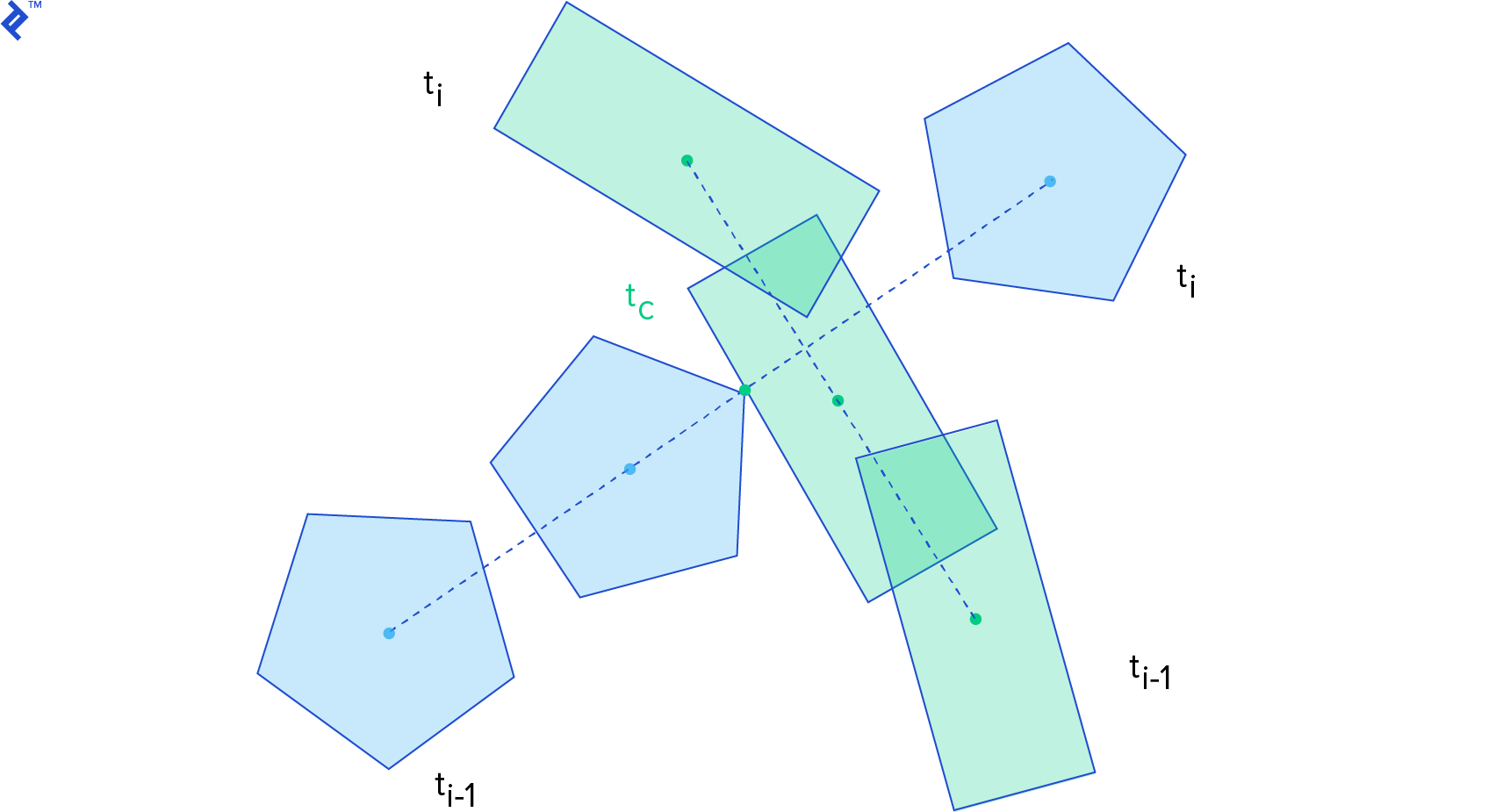

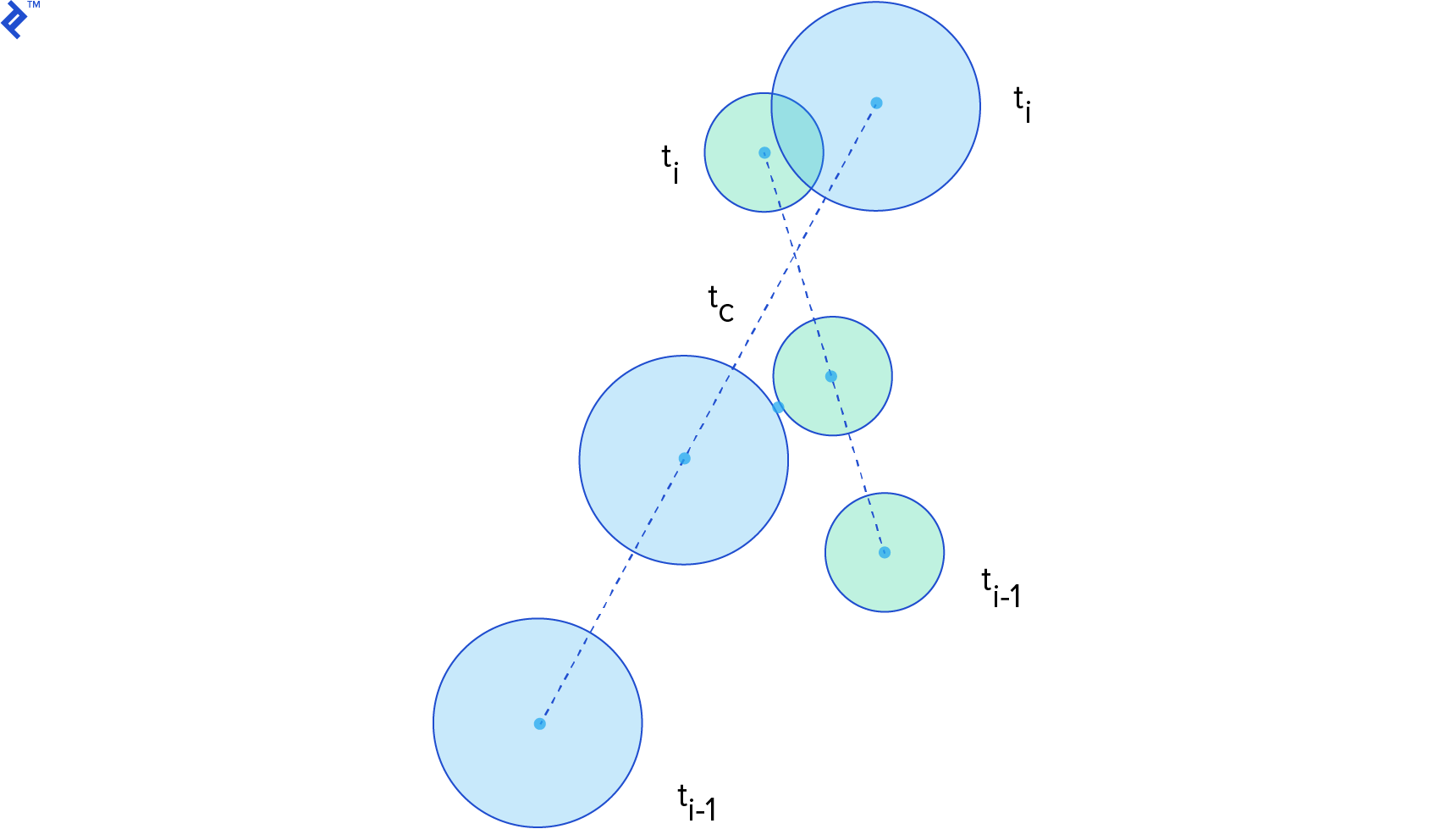

Continuous collision detection techniques attempt to find when two bodies collided between the previous and the current step of the simulation. They compute the time of impact, so we can then go back in time and process the collision at that point.

The time of impact (or time of contact) tc is the instant of time when the distance between two bodies is zero. If we can write a function for the distance between two bodies along time, what we want to find is the smallest root of this function. Thus, the time of impact computation is a root-finding problem.

For the time of impact computation, we consider the state (position and orientation) of the body in the previous step at time ti-1, and in the current step at time ti. To make things simpler, we assume linear motion between the steps.

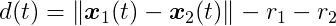

Let’s simplify the problem by assuming the shapes are circles. For two circles C1 and C2, with radius r1 and r2, where their center of mass x1 and x2 coincide with their centroid (i.e., they naturally rotate about their center of mass), we can write the distance function as:

Considering linear motion between steps, we can write the following function for the position of C1 from ti-1 to ti

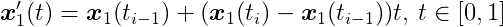

It is a linear interpolation from x1(ti-1) to x1(ti). The same can be done for x2. For this interval we can write another distance function:

Set this expression equal to zero and you get a quadratic equation on t. The roots can be found directly using the quadratic formula. If the circles don’t intersect, the quadratic formula will not have a solution. If they do, it might result in one or two roots. If it has only one root, that value is the time of impact. If it has two roots, the smallest one is the time of impact and the other is the time when the circles separate. Note that the time of impact here is a number from 0 to 1. It is not a time in seconds; it is just a number we can use to interpolate the state of the bodies to the precise location where the collision happened.

Continuous Collision Detection for Non-Circles

Writing a distance function for other kinds of shapes is difficult, primarily because their distance depends on their orientations. For this reason, we generally use iterative algorithms that move the objects closer and closer on each iteration until they are close enough to be considered colliding.

The conservative advancement algorithm moves the bodies forward (and rotates them) iteratively. In each iteration it computes an upper bound for displacement. The original algorithm is presented in Brian Mirtich’s PhD Thesis (section 2.3.2), which considers the ballistic motion of bodies. This paper by Erwin Coumans (the author of the Bullet Physics Engine) presents a simpler version that uses constant linear and angular velocities.

The algorithm computes the closest points between shapes A and B, draws a vector from one point to the other, and projects the velocity on this vector to compute an upper bound for motion. It guarantees that no points on the body will move beyond this projection. Then it advances the bodies forward by this amount and repeats until the distance falls under a small tolerance value.

It may take too many iterations to converge in some cases, for example, when the angular velocity of one of the bodies is too high.